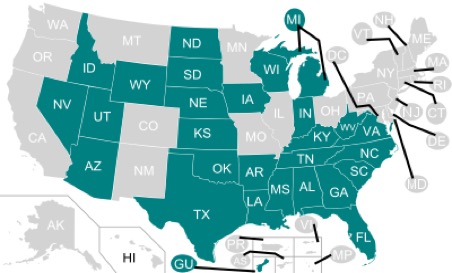

Figure 1. Right-to-Work states (in green).

Unfortunately, these simplistic approaches are not likely to be revealing. Publicly stating its decisional criteria can subject a company to legal challenge. Legal implications aside, a manufacturer may not want to disclose the true reason for choosing one location over another (e.g., for competitiveness reasons). Finally, a company executive may choose to provide an alternative rationale for strategic reasons.

Simple correlations of new factories with RTW states presumes that RTW states are not systematically different from non-RTW states, but this is false. For decades, RTW states were geographically concentrated. The first states to adopt RTW (all before 1958) were in the south (every state that was a member of the Confederacy is a RTW state) and systematically different from northern states in terms of, for example, transportation infrastructure. The establishment of the interstate highway system would be expected to attract manufacturing to the south, even in the absence of a RTW law. Other factors unrelated to policy also would be expected to confound any positive correlation between RTW and new manufacturing growth.

So how do we know if RTW laws affect the siting decision of manufacturers? A review of the academic literature shows that a well-designed study takes one of the following approaches:

- Looks at manufacturing activity near state borders. Many potentially confounding factors unrelated to policy can be eliminated just by focusing on differences that arise when crossing from one state to another.

- Compares the chosen site location with the runner-up location. Larger companies will often reveal a short list of possible locations in order to generate competing offers of incentives (e.g., tax breaks, subsidies) from local or state governments. Comparing the winning location to the runner-up location creates a fair comparison.

- Accounts for systematic differences between RTW and non-RTW states using one of several known statistical methods.

Empirical Evidence

Very few well-designed studies have been conducted to explore the location decision, but the results are enlightening.

Schmenner et al. (1987) used a database of 164 new plant openings by large companies between 1970 and 1980. Plant managers were surveyed to provide details about their plant and the location decision. The researchers modeled the siting decision as a two-stage process, where a subset of states were first chosen before a more detailed analysis was done to support a final decision. RTW was found to be a significant factor in favor of a state being eliminated from consideration in stage 1. No single factor was found to be significant in explaining the stage 2 (final) location decision. The researchers concluded that RTW is used by many major companies as an initial screen.

This staged approach to making a siting decision is widely acknowledged and reflected in more recent research. For example, Greenstone et al. (2010) compared the impact of a new manufacturing plant on nearby industry (i.e., the winning location) to that of manufacturing in the runner-up (i.e., losing) location.

Holmes (1998) looked closely at manufacturing growth at the border between adjacent states: those with pro-business policies and those with anti-business policies. The enactment of a RTW law was used as a proxy for pro-business policies in a state. His careful analysis showed a clear difference—the manufacturing share of total employment increases by about one-third when crossing from an anti-business state to a pro-business state. The study design, however, cannot be used to distinguish among the various pro-business policies or policy variables in a state (e.g., pro-business governors and/or state legislatures, low corporate tax rates, etc.).

Holmes (2014) describes why unions continue to influence manufacturing location by focusing on siting decisions by two large US exporters: Boeing and GE. He finds that recent siting decisions by both companies reflect the influence of unions and unionization. In particular, both companies make location decisions for new plants based on the presence or absence of a state RTW law. However, for capacity expansions at existing plants, companies may choose a location in a non-RTW state if the perceived benefits (higher productivity due to the presence of both R&D with manufacturing at an existing site) outweigh the perceived costs (related to greater unionization). Holmes’ analysis is intriguing and worthy of testing across a larger sample of firms and industry sectors.

Future Research

Given our current understanding, there are several policy-relevant questions that are worthy of additional research, such as:

- How important is RTW versus other pro-business policies in attracting manufacturing to a state? How does the answer differ across manufacturing subsectors (e.g., those with the highest percentage of organized labor)?

- Which of the various public indices of “pro-business state policy climate” are best? Perhaps the presence or absence of a state RTK law is not the best proxy.

- How impactful is a RTW law on outcomes of interest--on unionization, on wages, on employment, on productivity? And how does this differ across subsectors of manufacturing (e.g., capital-intensive versus labor-intensive manufacturing)?

These questions, if answered with greater confidence than we have today, would greatly aid our understanding of how domestic manufacturers make siting decisions.

Conclusion

Even if RTW had no impact on siting a new factory, one would still expect to see a strong positive correlation between manufacturing growth and RTW due to systemic differences between RTW and non-RTW states. Research must therefore be carefully designed to address this issue. Such studies show that pro-business policies (including RTW) positively impact the siting decision of manufacturers. Furthermore, RTW matters more in the initial screening process when manufacturers narrow their locational choices than when making a final siting decision.

Presuming RTW laws do matter when siting a new factory, an important question is the impact on unionization rates, worker wages, and various measures of manufacturing performance (productivity, etc.). If there is very little impact, then perhaps a RTW law is not the best screening tool to use when making a siting decision. For a broader perspective on the impact of RTW, see review articles in the academic literature (Moore 1998) and more recently published peer-reviewed studies, such as Stevans (2009) on the impact of RTW laws on business and labor markets, Eren and Ozbeklik (2016) on the impact of Oklahoma’s RTW law on labor market outcomes, and Hicks et al. (2016) on the impact of RTW on productivity and population growth.

The future of RTW legislation in the US is unclear. Some states adopted RTW laws after the GOP captured control of many state legislatures and governorships in the landslide election of 2010. This process could reverse itself if the Democrats have a landslide victory in November 2018, since labor unions are a core constituency of the Democratic Party. On August 7, 2018, Missouri voters rejected the state’s recently enacted RTW law, 67% - 32%, via referendum after a concerted campaign by organized labor. It is an open question whether this labor victory will reverberate beyond Missouri.

Peer Reviewers: Mark M. Levin, Clinical Associate Professor, School of Public and Environmental Affairs, Indiana University, and Chad Moutray, Chief Economist, National Association of Manufacturers

For Further Reading:

Eren, Ozkan and Ozbeklik, Serkan. 2016. What do Right-to-Work Laws Do? Evidence from a Synthetic Control Method Analysis, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 35 (1), 173-194.

Greenstone, Michael, Richard Hornbeck and Enrico Moretti, 2010. Identifying Agglomeration Spillovers: Evidence from Winners and Losers of Large Plant Openings, Journal of Political Economy,118 (3): 536-598.

Hicks, M.J., Lafaive, M., and Devaraj, S. 2016. New evidence on the effect of right-to-work laws on productivity and population growth. Cato Journal, 36 (1), 10-120.

Holmes, T.J. 1998. The effects of state policies on the location of industry: Evidence from state borders. Journal of Political Economy. 106, 667-705.

Holmes, T.J. 2013. New manufacturing investment and unions. Economic Policy paper 13-2. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Moore, W.J. 1998. The determinants and effects of right-to-work laws: A review of the recent literature. Journal of Labor Research,19 (3), 445-469.

Moore, W.J. and Newman, R.J. 1985. The effects of right-to-work laws: A review of the literature. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 38, 571-585.

National Association of Manufacturing. 2017. 20 Facts about Manufacturing. http://www.nam.org/Newsroom/Top-20-Facts-About-Manufacturing/

Schmenner, R.W., Huber, J.C., and Cook, R.L. 1987. Journal of Urban Economics,21, 83-104.

Stevans, L.K. 2009. The effect of endogenous right-to-work laws on business and economic conditions in the United States: A multivariate approach.

Review of Law and Economics,

5 (1), 595-614.