Sectoral Bargaining

Download as PDF

John D. Graham and Kenneth G. Dau-Schmidt

One interesting difference between the remaining Democratic U.S. presidential candidates relates to U.S. labor law. Both seek to strengthen labor unions but they differ on sectoral bargaining. Bernie Sanders favors it while Joe Biden is more cautious, pledging only to study it.

Under sectoral bargaining, all workers (union and non-union) in an industry sector are covered by the terms of a sector labor agreement. Unlike the United States, sectoral bargaining is common in several continental European countries, including those with high (e.g., Sweden) and low (e.g., France) rates of union membership.

To operationalize sectoral bargaining, an association of companies typically negotiates with an association of unions. The role of the national government varies considerably across different countries, from passive observer to active participant.

In this issue, we explore what sectoral bargaining might mean for the U.S. manufacturing sector and what the prospects for such a reform might be under a new administration and Congress.

U.S. Labor Law and Practices

In the United States, sectoral bargaining was practiced briefly in the 1930s pursuant to the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933. But in 1935 it was replaced by enterprise-level bargaining, where labor agreements are negotiated on a company-by-company basis, under the National Labor Relations Act. Under current US laws, the employer has an obligation to “bargain in good faith” only if a majority of employees in “an appropriate bargaining unit’ indicate their desire to be represented by a union, usually through an election supervised by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). An appropriate bargaining unit can be as small as a single type of worker at a single plant, if these workers share sufficient “community of interest.”

Though not required, multi-employer bargaining can be undertaken if employers and unions voluntarily agree. There is some US experience with multi-employer bargaining in the steel, automotive, trucking, construction, and mining industries but, as membership in unions declined, multi-employer bargaining also declined and today the practice is common in only a few sectors (e.g., hotel employees).

Critique of Current Laws

Critics of current US labor law argue that employee organizing is too burdensome and that too few workers receive the benefits of union representation. US union election procedures allow management many opportunities to delay the process and discourage unionization. Sometimes management illegally intimidates union supporters and threatens punishment of workers who join unionization efforts. Tesla’s management, for example, was recently reprimanded by the NLRB due to a tweet that threatened retaliation against workers who joined pro-union activities.

Even when unions are established, US labor law provides mechanisms for management to avoid negotiations. Because bargaining is done on a firm or even sub-firm level, employers can escape union organization by reassigning or sub-contracting work to non-union workers, or reorganizing production so that the workers are “independent contractors” and thus not covered by labor laws and prohibited from organizing under antitrust laws.

The question of whether American workers want to be represented by a union is more complicated than it might seem. The United Autoworkers (UAW) has made several failed efforts to organize US plants owned by Japanese, German, and Korean vehicle manufacturers. Union detractors argue that these workers do not want union representation. However, public opinion polls provide a somewhat different perspective. Almost 50% of American workers say they would vote for union representation if provided an opportunity to do so. In the US economy as a whole, unions represent about 10% of all US workers and 8% of manufacturing workers.

The Case for Sectoral Bargaining

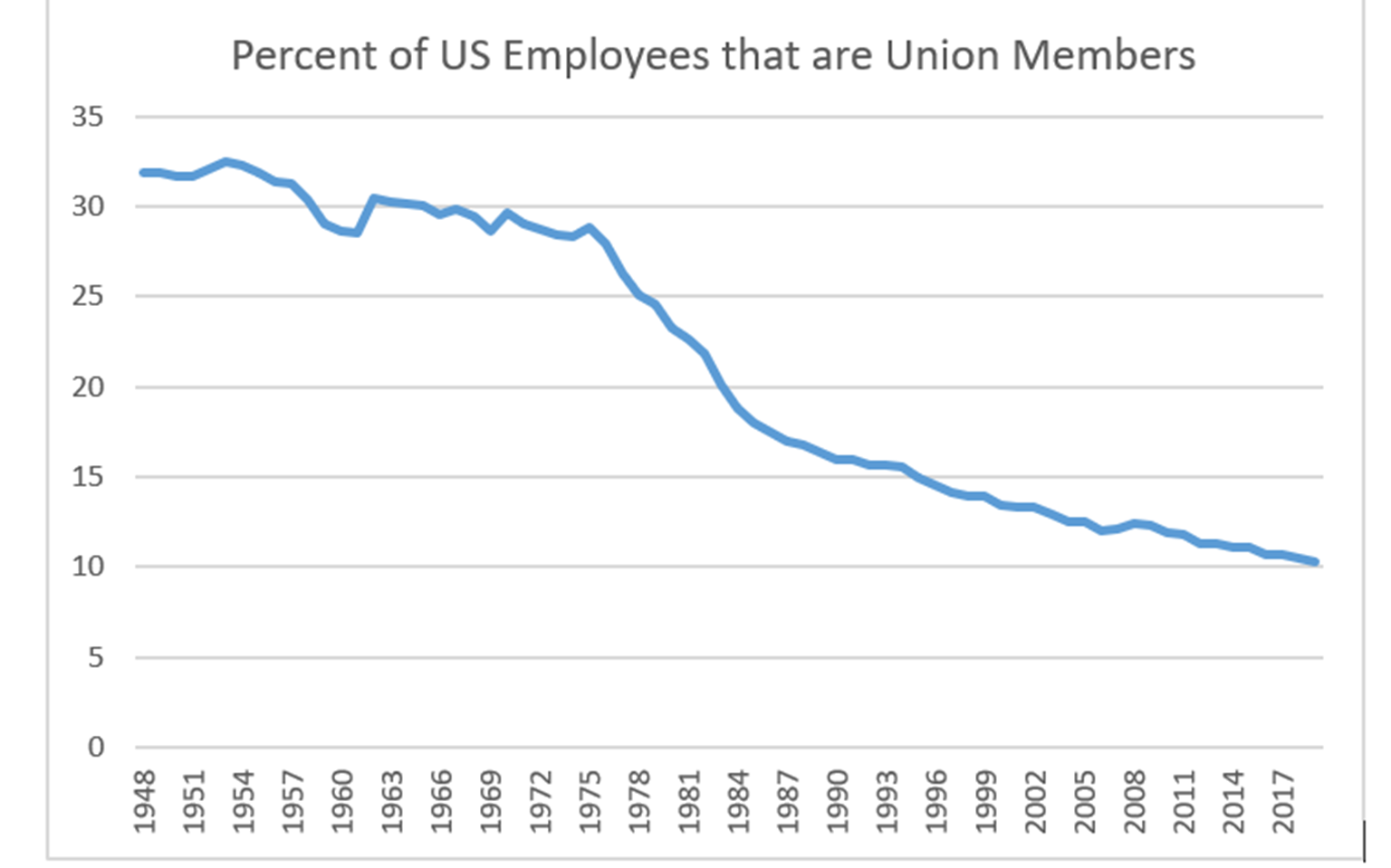

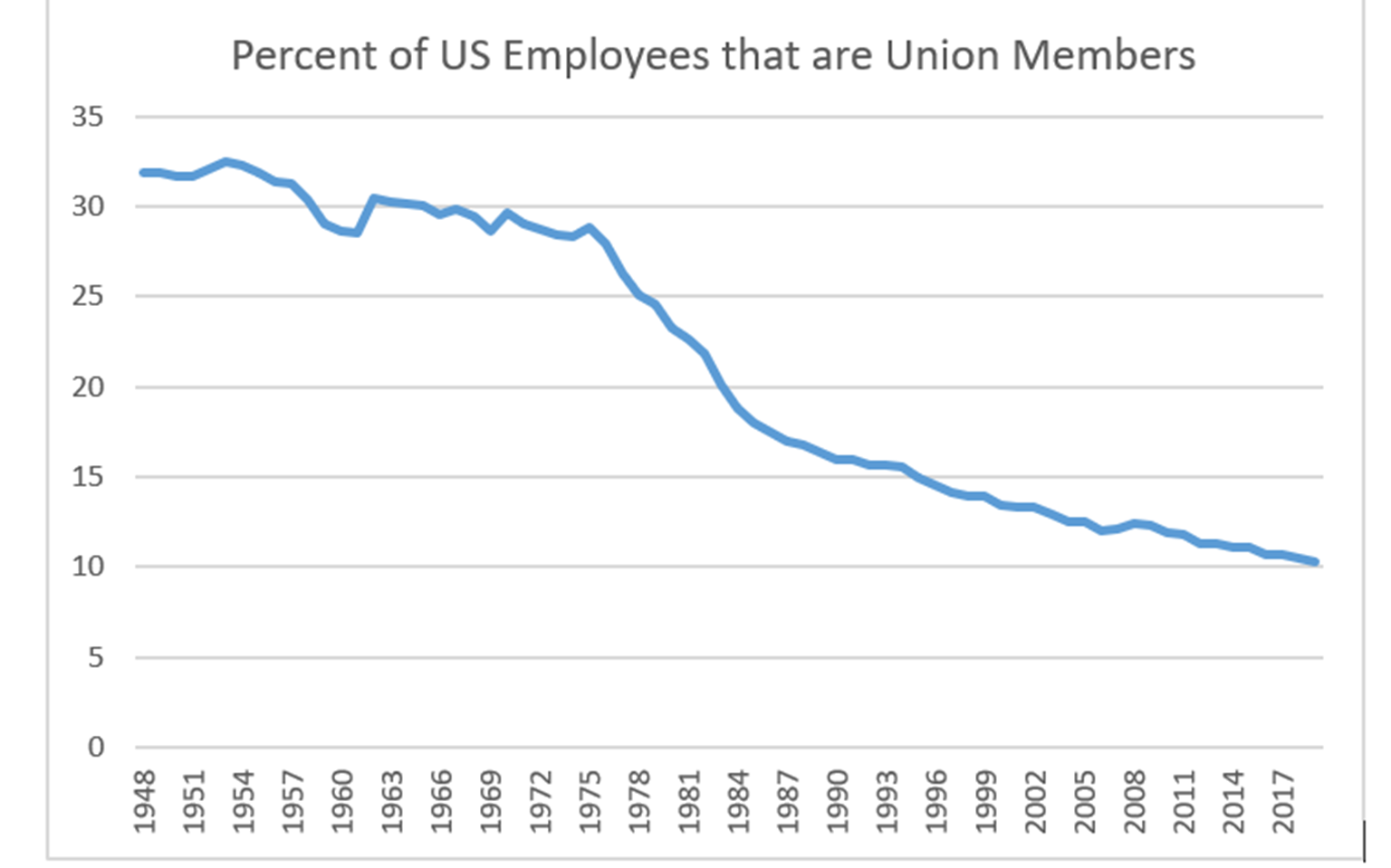

In US manufacturing, union membership has experienced a long-term decline (Figure 1) while union workers earn more than their non-union peers. Advocates of sectoral bargaining argue that it will reverse these trends. It would facilitate a uniform, minimum framework for wages and benefits. By equalizing union and non-union wages, sectoral agreements would lessen employer resistance to union organization and lessen incentives for employers to subcontract or reorganize work to avoid paying union wages. If sectoral bargaining is successful in raising and standardizing wages, it will decrease income inequality.

To the extent that the government participates in sectoral negotiations, it can help mediate conflicts, moderating excessive worker or employer demands, and coordinate national industrial policies. In Germany, the government uses its influence in sectoral bargaining to coordinate worker training and plan strategies to help the country’s workers and companies succeed. Germany’s relative success in the global economy (it offers higher wages than the United States and has a positive balance of trade) may be related -- at least in part -- to its system of tripartite sectoral bargaining.

Based on European experience, sectoral bargaining does not necessarily eliminate bargaining at the company or facility level. The national sectoral agreement typically supplies the minimum terms or patterns regarding wages and benefits; specific firms or plants may or may not be free to go beyond the minimum. Issues that are unique to specific companies or plants (e.g., health and safety) would still be addressed through enterprise-level and facility-level bargaining.

Figure 1. Percentage of U.S employees that are Union Members.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Case against Sectoral Bargaining

In a setting where US manufacturing shifts to sectoral bargaining, companies will reassess where and how they produce. Critics argue it will make US manufacturing less competitive.

If sectoral bargaining raises wages, this might discourage start-ups in the United States and give manufacturers incentive to locate jobs overseas. For example, if Tesla had to pay wages under a contract similar to the recent UAW agreements with the Big Three automakers, then it might shift more of its production away from the “Gigafactory” near Reno, Nevada to its new plant in Shanghai, China. Similarly, if the “transplant” Japanese, Korean, and German automakers were covered by a contract that equalized wages among US automakers, they might shift some US production to Mexico. Even the “Big Three” US automakers—already covered by UAW contracts—might shift production to lower-wage workers overseas if their competitors take this action.

The implications are more complex when one considers international trade policy. If US labor organizations regain political strength under sectoral bargaining, they may urge US politicians to impose tariffs or quotas on importers that are producing in low-wage economies and/or economies with lesser environmental standards. Under these conditions, US parts manufacturers may capture greater market share because tariffs or quotas will have been slapped on imported parts from Mexico and China. However, insofar as the US makes greater use of tariffs and quotas, one can expect retaliation from other countries that might hurt American manufacturers that have export-oriented businesses. This aspect of the impact of sectoral bargaining on trade policy is necessarily speculative. The European countries that have sectoral bargaining and stronger unions are all low-tariff countries, with free-trade obligations under the World Trade Organization, but sometimes use nontariff barriers to accomplish their protectionist goals.

Detractors also argue that unions make it more difficult and time consuming for companies to be nimble and opportunistic as market conditions and technologies change, creating a barrier for innovation. Small businesses may have more difficulty under sectoral bargaining influenced by larger firms in the sector. Under sectoral bargaining, any such impediments to innovation would impact an entire sector rather than individual firms.

Political Outlook

Because sectoral bargaining would require changes to US labor law, political analysis needs to consider the partisan composition of Congress as well as the White House. If the Republicans reach a majority of either the Senate or House after the 2020 election, it seems highly unlikely that major labor law reform could pass. It is possible that the Democratic Party could secure majorities in the House and Senate in the 2020 elections while also capturing the White House. Under that scenario, labor law reforms are likely to be considered, but even then majority support would depend on support from the most moderate legislators in the Democratic Party. Moreover, a GOP-led filibuster threat in the Senate is likely and, under current Senate rules, a vote of at least 60 of the 100 Senators would be necessary to bypass the filibuster threat. Previous efforts at labor law reform under Presidents Harry Truman, Lyndon Johnson and Barack Obama were blocked in the Senate, where the rules require supermajorities to legislate. On the other hand, the rules of the Senate can be changed with a simple majority vote, and a new Democratic-majority Senate in 2021 might vote to remove supermajority requirements.

For further reading:

Steven Greenhouse, 2019. A to F+: Grading the Presidential Candidates on Their Labor Plans Worker rights are shaping up a key issue in 2020. Who has the best ideas? NY Magazine Intelligencer, September 23.

Thomas Kochan, Duanyi Yang, Erin L. Kelly, and Will Kimball, 2018. Who wants to join a union? A growing number of Americans, The Conversation, August 30.

David Madland and Malkie Wall, 2020. What Is Sectoral Bargaining?, Center for American Progress, Washington, DC.

John D. Graham is Professor, Paul H. O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs, and Kenneth G. Dau-Schmidt is Willard and Margaret Carr Professor of Employment and Labor Law, Maurer School of Law, at Indiana University.

Peer Reviewers: David Madland, Senior Fellow, Center for American Progress, and Kristin Dziczek, Vice President - Research, Center for Automotive Research